Learning any language is a challenge.

If you’re a native speaker of a European language and you’ve learned another European language, you might think you’ve got languages nailed down.

The Chinese writing system is a whole different animal, and it’s one of the many aspects of the language that make it harder to learn.

By now, you’ll probably be aware of the existence of Chinese characters, or 汉字 (Hànzì).

But what’s the difference between components, radicals, characters, and words?

Simply put, in Mandarin Chinese, words form sentences, characters form words, and components and radicals form characters.

Contrary to what many Chinese learners believe, there is only ONE radical in every Chinese character.

Seriously, What are Chinese Radicals?

部首 (bùshǒu) means ‘section head’ and is translated as ‘radical’ in English.

Don’t ask me why, otherwise we’ll never get to the end of this post.

But what does a radical actually do other than confuse you?

- Radicals allow you to search for a character in a dictionary. I’ve written a post on how to do this here.

- Radicals can help hint at the characters meaning.

- Radicals sometimes hint at the pronunciation.

Chinese radicals are what we could think of as the base component of each character.

It is usually the leftmost part of the character, but definitely not always.

Let’s take a look at the component 口 (kǒu), meaning ‘mouth’.

- 吃 (chī) – meaning ‘eat’

Here you can see that 口 is on the far left. In this example, 口 is the radical.

- 语 (yǔ) – meaning ‘language’

With 语 we can see 口 in there, but is it the radical or just a component? If you said it’s a component, give yourself a red star! In this case, 讠is the radical.

- 讠(radical) + 五 (component) + 口 (component) = 语

HEADS UP: There is a radical in every character, even if the radical is the character!

Is a radical always on the left-hand side of a character?

No.

When trying to find the radical of a character, try to remember the following:

- The radical is usually on the left in a horizontal character (such as 妈 – radical is 女)

- The radical is usually at the bottom of a vertical characters (such as 字 – radical is 子)

- Some characters have both horizontal and vertical components. In these cases, radicals usually span the length or height of the character. For example, (脖 – radical is 月) and (想 – radical is 心).

- If you really have no idea what I’m talking about, you can find out the radical of any characters with Arch Chinese right here.

HEADS UP: We know that a radical can be a character on its own, but radicals can also look different when they’re a part of another character!

Let’s take a look at some examples of this.

| Radical | Radical as character | pinyin | meaning | examples |

| 亻 | 人 | rén | person | 你 you (nǐ) | 他们 they (tā men) |

| 忄 | 心 | xīn | heart | 懂 understand (dǒng) | 情 feeling/emotion (qíng) |

| 氵 | 水 | shuǐ | water | 河 river (hé) | 洗 wash (xǐ) |

| 讠 | 言 | yán | language | 说话 talk (shuō huà) | 语言 language (yú yán) |

| 扌 | 手 | shǒu | hand | 推 push (tuī) | 拉 pull (lā) |

| ⻊ | 足 | zú | foot | 踢 kick (tī), | 跑 run (pǎo) |

How should I learn radicals and components?

Back in the day, understanding components and finding the radicals was vital to be able to find them in any dictionary.

Nowadays, the internet is there for any doubt we might have, and meanings can be found in seconds.

So is there any point in learning radicals these days?

If you want to make learning characters easier (I think we all do), then the answer is definitely YES.

Today, in simplified Chinese, there are 214 Chinese radicals and components. You can find a list of them here.

A surprising number of Mandarin learners skip learning radicals and components and go straight to memorising new words.

Can you learn new words without learning the radicals first? Yes, you can.

Do I recommend it? No, I don’t.

Why? Because I did this, and I wasted a lot of time by not learning the basics.

For complete beginners, my best advice is to acquire an app with SRS (Spaced repetition software) and simply spend a week or two getting familiar with all of the radicals and components.

If you need suggestions for a good SRS app, check this out.

Learning new words and characters through radicals and components

By now you understand what a Chinese radical is, why they are important, how to identify them inside a character, and how to learn them.

But how can we use them to study to learn new words and characters?

Repetition and association.

This is the basis of all learning processes, but it’s common practice for good reason – it works.

Each radical has an accompanying meaning, and usually, characters that feature this radical are related to this original meaning in some way.

But not always.

So, the best way to start practicing Chinese is to focus on one radical at a time, understanding its nuances, and then practicing with characters that include this radical.

Let’s use 子 (zǐ), meaning ‘child’, as an example:

| Radical | Character | Meaning | Word | Meaning |

| 子 | 孕 (yùn) | be pregnant, pregnancy | 怀孕 (huáiyùn) | pregnant, to have conceived, gestation, pregnancy |

| 子 | 季 (jì) | season, period, quarter of year | 季节 (jìjié) | season |

| 子 | 孝 (xiào) | filial piety, obedience, mourning | 校训 (xiàoshùn) | filial piety, to be obedient to one’s parents |

Now, you might be wondering a couple of things:

- What does ‘child’ have to do with seasons?

- It seems the character has the same meaning as the two-character combination that forms the word. Why do I have to learn a two-word combo?”

Firstly, as I said earlier, not all radicals relate to the meaning of the characters they feature in.

Secondly, you have to learn character combos because you just do, OK? The vast, vast majority of words in Chinese are 2-3 characters combinations.

However, for now, learn radicals and components.

Why not get started with the following radicals and components and then move on to the characters they’re part of?

- 人 (pronouns, basic greetings)

- 子 (education, people)

- 宀 (house, family)

- 言 (languages)

- 囗 (countries)

- 阝 (directions)

- 辶 (motion)

- 疒 (illnesses)

- 心 (thoughts and feelings)

If you’re really interested in the breakdown of Chinese characters, check out the following…

Phonetic-semantic compounds

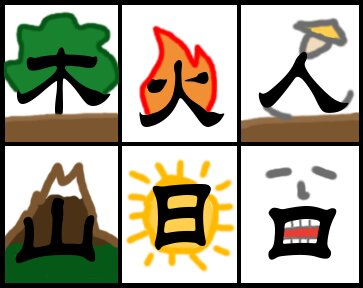

Back in the day we all wore leaves for underpants, had big beards, and drew on walls to communicate.

Things have changed a lot but Interestingly enough, around 5% of modern-day Chinese characters still contain pictographs.

What often isn’t spoken about, however, is that phonetic-semantic components make up almost 80% of all characters in Mandarin Chinese.

Learning to recognise phonetic-semantic components is a very useful skill. it can be used as another tool in your arsenal as you aim to hasten the speed at which you learn and understand new characters.

If you want to learn more about it, Olle Linge over at Hacking Chinese has written a very helpful guide.

Summary

- Around 214 radicals and components make up nearly all Chinese characters in use today.

- Radicals can be described as the base component of each character.

- Radicals and components can change in appearance depending on where they are in a character.

- Radicals and components can often form individual characters on their own.

Further Reading

- 100+ MANDARIN LEARNING RESOURCES: THE FASTEST WAY TO FLUENCY

- LEARNING CHINESE: 15+ LISTENING TOOLS PERFECT FOR BEGINNERS

- THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO LEARNING CHINESE IN CHINA

- THE 24 BEST MANDARIN STUDY RESOURCES FOR BEGINNERS

- 14 REASONS WHY YOU SHOULD LEARN MANDARIN CHINESE

- IS IT EASY TO LEARN MANDARIN CHINESE?

- THE 21 BEST APPS TO LEARN CHINESE

- STUDYING MANDARIN AT A UNIVERSITY IN CHINA: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW